Mario-Andreas von Lüttichau

Italy is what Matters: Max Peiffer Watenphul, from the Bauhaus to the Villa Massimo

Von der Heydt-Museum Wuppertal

It was Alfred Salmony, curator of the East Asian Museum in Cologne, who described the spirit of the young Max Peiffer Watenphul’s early landscapes and still lifes as evincing a “different kind of being, playful but symbolically linked, somehow long familiar and yet new.” Alfred Salmony, “Max Peiffer Watenphul,” in Das Kunstblatt,vol. 5 (1921), p. 272. Everything seems self-evident in Max Peiffer Watenphul’s first paintings in Weimar, such as the church with the mighty bell tower and the two large crosses above the idyllic site, nestled amidst the thick foliage of trees, enclosed by expanses of nature and park landscapes. A white sheep and a black horse populate the sparsely blooming meadow, as if by coincidence. White lilacs rise up into view. Dark smoke, bundled as though shot out of a canon, rises into the slightly cloudy sky, and there is written in yellow letters above this seeming paradise: WEIMAR. Is this how we are to imagine the place that achieved its first cultural blossom with Lucas Cranach the Elder? The place that became the genius loci of classicism with Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich von Schiller? Where Johann Gottfried Herder preached his idea of humanistic education and his Ideas for a Philosophy of the History of Humanity? Where Friedrich Nietzsche recorded his reflections on the non-being of life? Where art opened a new conceptual realm? Where, at the beginning of the twentieth century, the diplomat and aesthete Harry Graf Kessler founded the Deutscher Künstlerbund and was forced to leave following the public presentation of “scandalous” drawings by Auguste Rodin? Where the architect Walter Gropius, as successor to the virtuoso Henry van de Velde, established a school of teachers and teaching that has had a lasting influence? Weimar, in short, is understood as an exclamation mark that reflects everything and brings it to a worthy conclusion: This is how the twenty-four-year-old Peiffer Watenphul, a doctor of laws and budding artist, felt and saw that seemingly innocent place, that became, soon after the first world-encompassing tragedy of war and the dissolution of the German Empire, the center of the first young republic, and thus, still a vision, dreamy, intimate, and aloof from the real.

from the Maple Tree, 1920,

Von der Heydt-Museum Wuppertal

“I have painted a new painting, the maple leaf,” Max Peiffer Watenphul recounted in a Christmas letter from Weimar in 1920 to his close friend Maria Cyrenius in Salzburg. Maria Cyrenius (1872–1959), a student of Johannes Itten’s at the Bauhaus, had her own enamel workshop in Salzburg from 1921 on. Peiffer Watenphul spent his summers there from 1922 to 1924. “Everything is gray, the drapery rose madder pink with white. The leaf burnt to green earth. Utterly majestic. Quite like the Chinese.” In the same letter, he recounts his impending journey to Hanover, together with his desire to visit the collector there, Herbert von Garvens-Garvensburg, patron of the arts and future gallerist. On Herbert von Garvens-Garvensburg (1883—1957), see Katrin Vester, “Herbert von Garvens-Garvensburg: Sammler, Galerist und Förderer moderner Kunst in Hannover,” in Henrike Junge, ed., Avantgarde und Publikum(Cologne, 1992), pp. 93–102. The letter evidences Max Peiffer Watenphul’s knowledge of contemporary happenings and the wide circle of artists, littérateurs, collectors, art historians, and gallerists through which he confidently moved. “Yesterday I came back from visiting Klaus. Klaus Gebhard (1896–1976), collector of Expressionists and patron of contemporary art, lived in Wuppertal until 1962, and in Munich thereafter. The days were beautiful but quite quiet in those rich and measured surroundings. I made the acquaintance of: Dr. Thormaehlen Ludwig Thormaelen (1889–1976), at the Nationalgalerie Berlin from 1914 until 1933, was assistant to Ludwig Justi and curator from 1925 on. He was part of Stefan George’s circle of friends and was close to Erich Heckel and other Expressionists. from the Kronprinzenpalais in Berlin and a friend of Thomas Mann’s, Dr. Bertram, Dr. Ernst Bertram (1884–1957), author and historian of literature, was associated with the Stefan George circle and wrote the book Nietzsche—Versuch einer Mythologie,1918 (Bonn, 1998). famous for his book Nietzsche …. It is very beautiful in my studio. There are three tall candles alight, each a meter long. The angel stands between them. Next to that, my magnificent African sculpture. Have you seen the new Picasso book from Piper & Co.? The new Picasso[s], realistic in a very kitschy way, and salon pink. Klaus gave me The Fashions of the Renaissance , a magnificent book, in particular the Carpaccio, the two courtesans. Gosebruch Ernst Gosebruch (1872–1953), head of the Essen art collections from 1909 on, and director of the Museum Folkwang Essen from 1922 until his resignation in 1933, was the initiator of one of the most modern museum concepts before the Third Reich. He was a patron of contemporary art and organized Max Peiffer Watenphul’s first museum exhibition in 1921. See Claudia Gemmeke, “Ernst Gosebruch,” in Henrike Junge 1992 (see note 3), pp. 11–117. in Essen has invited me to visit him tomorrow. Dr. Hagemann Carl Hagemann (1867–1940), collector of Expressionists and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner in particular, was a patron of contemporary art. See Karlheinz Gabler, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Dokumente(Aschaffenburg, 1980), p. 154. (who owns the Derains) is with him, and he is interested in me. Uhde Wilhelm Uhde (1874–1947), aesthete, author, art critic, collector, patron, and gallerist, lived in Paris from 1904 on, was married until 1910 to Sonia Terck, future wife of Robert Delaunay, was a friend of Picasso’s and Braque’s and a correspondent for Alfred Flechtheim and Herwarth Walden. See Heinz Thiel, “Wilhelm Uhde,” in Henrike Junge 1992 (see note 3), pp. 305–20. has sold more paintings of mine to Flechtheim. Alfred Flechtheim (1878–1937), grain merchant, aesthete, and art dealer, was passionately engaged on behalf of contemporary art, in particular Picasso, Braque, and Léger. He had galleries in Düsseldorf, Berlin, and elsewhere. See Alfred Flechtheim, Sammler, Kunsthändler, Verleger,exh. cat. Kunstmuseum Düsseldorf (Düsseldorf, 1987). Also a painting to Kolle, Helmut Kolle (1899–1931), privately educated as a painter, was close friends with Wilhelm von Uhde and lived continuously in Paris and Chantilly from 1924 on. See Helmut Kolle, Hartwig Garnerus, ed., exh. cat. Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus (Munich, 1994). a painting I gave him as a gift in 1916…. But now I am signing a contract with Flechtheim. I can get to Italy, after all, on 700 marks. And that is what matters.” See Max Peiffer Watenphul, Werkverzeichnis, vol. 1, Paintings and Watercolors, Grace Watenphul Pasqualucci and Alessandra Pasqualucci, eds. (Cologne, 1989), p. 17 (only quoted in part) and original letter in the artist’s papers.

Italy is what matters, the measure of things, and a small sketch in the letter—accompanied by the brief description of the important things—further clarifies Peiffer Watenphul’s artistic thinking, of reducing a composition to a few references, narrative but enigmatic: It is the encounter of an open book with letters and words that resist interpretation—OriLi LANO—a ripe pear next to the eponymous maple leaf, clearly decorating a gray table with a drawer, presumably a kitchen table, and all this in front of an authoritatively gray background that continues on behind the rose madder pink of a curtain bundled like a theater curtain.

Max Peiffer Watenphul addressed his varied life in Weimar on a number of occasions, not only in letters to Maria Cyrenius. He described the stimulating, entertaining, and sometimes exciting evening events, lectures, discussions, and concerts “with prominent poets, philosophers, and artists from Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. A reading by Else Lasker-Schüler I remember vividly. The Viennese contingent [meaning the pupils of Johannes Itten whom he had brought with him to Weimar] had decorated the hall with prayer rugs and Jewish candles. The little poetess with the gypsy-like face had an immensely dignified presence, and she spoke her poems, which moved us deeply. Her friend Theodor Däubler also read us his deep poems filled with visionary views. Franz Werfel came, as did his spouse Alma Mahler, the widow of the composer, who interested us very much. After all, she had been painted by Kokoschka, and she was very famous. For example, in the Double Portraitof 1912/13 (Oskar Kokoschka and Alma Mahler), Museum Folkwang Essen, owned at the time by the Hanover collector Herbert von Garvens-Garvenburg, with whom Peiffer Watenphul maintained contact (see note 3). Kokoschka’s Double Portraitwas moved to the Staatliche Gemäldegalerie Dresden in the mid-nineteen-twenties. In 1937, it was seized by the National Socialists as “degenerate.” After two subsequent changes of ownership, it came to the Museum Folkwang in 1976. The days in Weimar were always colorful, lively, and never boring.” Thus, the summary of the Bauhaus student, apparently content with his time there. Quoted in Bert Bilzer, Peiffer Watenphul(Göttingen, 1974), p. 8. Peiffer Watenphul also recounted that Burchartz, for example, had not begun painting his portrait as planned. Vally was also painting his portrait for a study: “I am to lie on a divan. Quite a lot of rose madder pink and white.” Herwarth Walden Herwarth Walden (born Georg Levin, 1878–1941), musician, littérateur, critic, collector, and gallerist, founded the “Verein für Kunst” in 1904 and the literary journal Der Sturmin 1910, which from 1912 until 1928, provided a gallery and platform for the avant garde of the first two decades of the twentieth century, Expressionists, Futurists, Cubists, “Sturm artists,” and others. See Georg Brühl, Herwarth Walden und “Der Sturm”(Leipzig, 1983). had visited the Bauhaus and Weimar, Alexander Archipenko was going to Berlin, and Oskar Schlemmer was then having a small exhibition, “immensely cultivated and enchanting. Lots of pink and silver. Gray, too, and pale brown.” Peiffer Watenphul was reading a gripping book by Eduard Graf von Keyserling, entitled, Abendliche Häuser (Evening Houses); Eduard Graf von Keyserling (1855–1918), Abendliche Häuser(Berlin, 1914). Alfred Salmony was going to publish an article about him in Das Kunstblatt , and Flechtheim had sent him a portfolio of lithographs by the painter Marie Laurencin, then decidedly en vogue in Paris. The artist was satisfied, all in all, with his summation: “So Weimar seems to be the liveliest place in the world.” See Werkverzeichnis,vol. 1 (see note 12), pp. 17–18.

Max Peiffer Watenphul was most closely linked artistically to Henri Rousseau, in whose work a new “depth and love for the world” found their fulfillment in the closing years of the prior century. In petty-bourgeois simplicity, Rousseau was ingeniously able to unite romantic longing and fairy tale-like mystery into exceptional and great works of art, with hardly an inkling of the significance and appreciation his work would later enjoy. It can hardly be claimed that Peiffer Watenphul had the naïve, unspoiled, lightheartedness of a Rousseau since his paintings were created with intention and through conscious design though preserving a gentle and sheltered awareness of life at the same time.

private collection

The importance of Rousseau, in particular in Germany, cannot have been unknown to the cultivated young artist. He must have been introduced to the work of Rousseau at the latest through his interest in the art journal Valori Plastici On the history of the journal Valori Plasticiand its artists, see Valori Plastici,exh. cat. Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Rome (Rome, 1998). and its leading artists, including Giorgio de Chirico, Carlo Carrà, and Giorgio Morandi, Paul Klee’s detailed declaration of belief in Rousseau, and the concept of Der Blaue Reiter. Works like the still life A Brown Leaf Has Already Fallen from the Maple Tree and Window with Curtains as well as portraits such as The Artist’s Mother in Profileand the Portrait of Maria Cyrenius,display the Rousseauian spirit although Peiffer Watenphul draws on the great realist’s gestures and objects without simply imitating his style of painting. Even in his early years, Peiffer Watenphul seeks and finds a personal style with great consistency. Yet, to view the paintings of Peiffer Watenphul the young Bauhaus student, educated in literature and art history, as simply naïve would be to misunderstand the work’s ingenious staging. These paintings are not so much based on a wholly credible reality in the broadest sense as they recreate from intense memory what has been seen, and they depict a mixture of ennobled and trivial pictorial worlds, regardless of whether the works in question are the portraits of the artist’s mother, the well-loved views from his studio window in Weimar, the Roman park landscapes inhabited by ancient reminiscences, and the bewitching, poetically arranged still lifes.

private collection

Composition peculiarity was all but obligatory for the still lifes Peiffer Watenphul painted in Weimar, that striking ordering of things drawn in overview, usually on a monochrome background, drawn in the greatest formal simplicity and not overlapping each other, and depicted, at best, in a nearly diaphanous, fragile materiality full of surreal poetry. The more or less banal objects are from the artist’s everyday surroundings, although figments of fantasy or, at least, generous heightenings of proportion can also be inferred. Now and then these otherwise so brittle and simple forms mutate into precious things and are brought into the scene in a nearly noble and emblematic fashion. The artist proceeds in similar fashion with the still lifes expanded into space (usually his studio in Weimar), with the view conveyed into a real environment, and the visual concept, the artist’s enclosure, conveyed into a purported reality.

Sprengel Museum Hannover

Perhaps it was in this light that Peiffer Watenphul observed the metaphysical concept once described by Giorgio de Chirico, according to which everything has two aspects: “a normal one that we almost always see and which is seen by other people in general; the other, the spectral or metaphysical which can be seen only by rare individuals in moments of clairvoyance or metaphysical abstraction. ” He continued: “A work of art must relate something that does not appear in its visible form. The objects and figures depicted in it must relate, as it were, poetically, something distant from them and which their material forms hide from us.” Giorgio de Chirico, “Sull’arte metafisica” (Rome, 1919), quoted in Walter Hess, Dokumente zum Verständnis der modernen Malerei(Hamburg, 1956), p. 111.

Museum der Bildenden Künste Leipzig,

loan from a private collection

Peiffer Watenphul also changes the idea of nature and its natural proportions, for example, in the reproduction of interior spaces, landscapes, and gardens and in the idea of streets and squares, which sink into a dreamy, possibly melancholy vision more than they intend to make a visual reality apparent or topographically visible in painting. The titles of paintings such as Cemetery in Weimar and Villa Massimo in Rome often make reference only to the real scene of what is experienced. They awaken a glimmering of an idea of the actual place in one’s memory, connected with a melancholy mood that hangs over the empty streets, squares, and gardens while emphasizing the feeling of the mysterious and the enigmatic.

Sprengel Museum Hannover,

loan from a private collection

Peiffer Watenphul plays at placing still lifes and garden landscapes alongside one another in sometimes strange relationships, and also placing them in the foreign surroundings of painted interiors that we do not find normal in our customary way of thinking. Describing the changed perception of space and the artistic conception of matter, de Chirico wrote that “in painting … we construct a new metaphysical psychology of things.” Ibid., quoted in Theories of Modern Art, ed. Herschel B. Chipp, trans. Joshua C. Taylor (Berkeley, 1968), p. 452.

Werner Haftmann has drawn attention elsewhere in this context to the tragic solitude of everyday life and to the mysterious existence of what goes unnoticed, but is then brought into the foreground, there to stimulate and trouble our recollection over time.

Peiffer Watenphul’s landscapes of the city of Weimar and the parks of Rome are to be understood in the same way in those instances in which the intermingling of strictly applied realism and proportion-negating relations of scale cause a puzzling effect, and enchanting reality alongside the expression of the mysterious at times contains within itself the aspect of romantic memory attained by Caspar David Friedrich.

This is in no way a look back into the preceding century of Biedermeier and Romantic thinking. Instead, influenced by his encounter first with the Munich Pinakotheks and then with the treasures of painting and art in Weimar, the young Peiffer Watenphul recognized the path toward orienting himself, after the end of the Expressionism to which he responded only with his “Mexico paintings,” toward classicisms in the spirit of objectivity. In particular, he reflected the juxtaposition of the Giottoesque in a reserved simplicity and order, and represented the world and its connections simply and symbolically through traditional principles. He could reorder things nonetheless, for example, by exchanging the treasures and luxuriant arrangements of past centuries’ still lifes for common and simple objects of everyday life while, at the same time, affording these simple forms the same meticulous attention in their pictorial formulation as executed by Alexander Kanoldt and Giorgio Morandi in metaphysical aesthetics. This applies equally to the rediscovery of architecture as an inspirational carrier of meaning and symbolic vocabulary in poetically romantic landscapes. To the work of the artists associated with the Valori Plastici group and the New Objectivity, with their simplicity and their exotic and many-layered visual metaphors, Peiffer Watenphul added an additional aspect of a painting that was seemingly naive, but borne by poetry and kindness.

Max Peiffer Watenphul’s Weimar works follow a tendency widespread in German art after World War I against abstraction and Expressionism; he assigned a leading role to the object’s “outer” shell and the contours’ sharpness. This predominantly objective sobriety and simplification in representation returns again to Rousseauian pictorial thinking, even if the moment of unlocking a visible reality, the self-willed and obvious joining of “pure” painting with “magic” realism took on a modern interpretation. An avowal of Neoclassicism can be recognized setting in for Peiffer Watenphul in the late nineteen-twenties and in particular during his stay at the Villa Massimo in Rome in 1931 and 1932. This was no coincidence. As head of the preliminary course at the Bauhaus from October 1919 on, Johannes Itten demanded not only the study of doctrines of proportion, color, and form, but also analyses of paintings of the artists of the Renaissance. A study by Peiffer Watenphul made from a Nativity by Fra Angelico survives in the Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin. Illustrated in Max Peiffer Watenphul Werkverzeichnis, vol. 2, Drawings, Enamel Works, Textiles, Graphic Art, Photography, Grace Watenphul Pasqualucci and Alessandra Pasqualucci, eds. (Cologne, 1993), cat. no. Z 13; see also additional Bauhaus studies reproduced there, cat. no. Z 7ff. The artist’s early and lasting admiration for the work of the fresco painter Piero della Francesca is also attested. The students at the Bauhaus were urged to study Weimar’s rich collections, above all, the paintings of the sixteenth century by Hans Baldung Grien, Lucas Cranach the Elder and Lucas Cranach the Younger, and Albrecht Dürer. Peiffer Watenphul’s fascination with delicate and characteristic portraits against such seemingly “modern,” monochrome backgrounds can be seen in his own works in Weimar, which also demonstrate his “weakness” for employing a detail-enamored but simplified naturalism to render such attributes as richly decorated and precious materials: fine jewelry, fragile flower arrangements, delicious bowls of fruit, and the like.

A momentous change took place in Peiffer Watenphul’s life when he deepened his encounter with contemporary art while still a law student in Munich, before he took his doctorate in church law in Würzburg in 1918 and was compelled to enter the military in the last days of the war, though he was never deployed. According to his own account, contemporary art still had something disreputable about it for him as a student, humanistically educated and conservative in character as he was. “My favorite thing,” wrote the law student, “was to go to the little Goltz art gallery on Briennerstrasse, where I went to the temporary exhibitions on the second floor. Such a visit had something daring and forbidden about it…. for there I saw things that were utterly new to me, that spoke to me mysteriously and that I was still unable to interpret.” Quoted in Bert Bilzer, Peiffer Watenphul(Göttingen, 1974), pp. 5ff.

Here, at the latest, in the Munich gallery that was perhaps the city’s most modern in orientation at the time, Peiffer Watenphul became acquainted with the unusual work of Paul Klee, The following possibilities existed for Peiffer Watenphul to have seen original works by Paul Klee in the time period under discussion in Munich. In 1917: autumn, “Sammelausstellung,” Galerie Neue Kunst Hans Goltz; third exhibition: “Neue Münchener Secession,” 18 works. In 1918: spring, “Neue Münchener Secession,” graphic art at Galerie Caspari, 30 works; summer, fourth exhibition: “Neue Münchener Secession,” 24 works. In 1919: summer, fifth exhibition: “Neue Münchener Secession,” 27 works; August, “Moderne deutsche Graphik,” Moderne Galerie Thannhauser, 10 works; September, “Sammelausstellung,” Galerie Neue Kunst Hans Goltz, 5 works. whose sense of poetry and fantasy he drank in, and whom he hoped would become his teacher. Klee declined to “educate” the lawyer into an artist, explaining that he was no teacher. He nonetheless recommended him to the painter Stanislaus Stückgold, possibly after seeing certain early works of Peiffer Watenphul that were influenced by tendencies of the New Objectivity. Here see a series of watercolors and drawings from 1915 and 1916, in Werkverzeichnis,vol. 2 (see note 21). Max Peiffer Watenphul was not happy with this recommendation, although his “early work,” for the most part, drawings and watercolors, had been created during his studies of law in the spirit of strict objectivity. Stückgold was certainly among the foremost representatives of the newly established Realists. His works were prized by Herwarth Walden and exhibited alongside those of Rousseau to bolster the Realist section at the First German Autumn Salon in Berlin in 1913. See Erster Deutscher Herbstsalon,exh. cat. Galerie Der Sturm (Berlin, 1913), cat. nos. 342–44, ill.: Portrait of Little Judith Wolfskehl.There were twenty-two works exhibited by Henri Rousseau. They were predominantly from private collections, and thus could not be sold, and were noted in the catalogue without illustrations. The student-teacher relationship between Peiffer Watenphul and Stückgold, never really begun, was very quickly over, perhaps owing to a dearth of sensitivity and poetry on Stückgold’s part. From time to time, Klee corrected works by the budding artist, who was eager for knowledge. Ultimately, Klee’s wife Lily suggested to Peiffer Watenphul that he go to Weimar, where the Bauhaus had opened in October 1919 under Walter Gropius. There, he would see Klee again as a future master in January 1921.

Certainly, there are many layers to the art historical preconditions for Peiffer Watenphul’s works in Weimar and in Rome in the early nineteen-thirties. He was strongly influenced by Giorgio de Chirico, Carlo Carrà, and Giorgio Morandi, the central figures of Valori Plastici. Other potential sources of inspiration for Peiffer Watenphul’s independent works include the Munich painters around Georg Schrimpf, Carlo Mense, and Alexander Kanoldt in particular. Another evident influence on the young artist was André Derain, including both Derain’s early still lifes and his Mediterranean landscapes, with their towering architectures. In the letter quoted at the beginning above, Peiffer Watenphul mentions the collector Carl Hagemann in connection with Derain’s works and a planned visit with the Essen museum director Ernst Gosebruch. Following the exhibition Aus den letzten drei Jahrzehnten der französischen Malerei (From the Last Three Decades of French Painting), Gosebruch succeeded in early 1914, with Hagemann’s help, in exhibiting three works by Derain in the Essen Kunstmuseum’s collection, including the 1912 painting View from a Window . The exhibition in January 1914 at the Kunstmuseum in Essen was entitled Aus den letzten drei Jahrzehnten der Französischen Malerei.By Derain: The Salt Pond of Martigues,1908; View of Cagnes,1910; and View from a Window,1912. The Folkwang was later given another painting by Derain from the Hagemann collection, the Still Life with Melon,1913. All of the Derains were expropriated in August 1937 as part of the “Degenerate Art” action. That painting had a markedly enduring effect on Peiffer Watenphul: the simple still life with plates and coffee pot on the table, the bare interior space and the expansive view into an ideal landscape with Mount Calvary, Since its sale at auction in Lucerne in 1939, this painting has been held by the Kunstmuseum Basel under the title Kalvarienberg(Mount Calvary). A second version of this composition exists, illustrated in André Derain,exh. cat. Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris (Paris, 1994), cat. no. 94, Nature morte devant le calvaire,1912. According to that catalogue, this painting was also in Hagemann’s collection. a river and a rowboat. Peiffer Watenphul reduced these impressions from Derain, shaping things in memory, and in keeping with the contemporary artistic approach in Weimar, making them simpler and significantly more withdrawn in form and expression. Derain also could have provided Peiffer Watenphul with an exemplary use of overview in still life painting, still unusual for the genre at the time. It cannot be ascertained for certain, however, whether Peiffer Watenphul knew Derain’s densely composed Still Life with Melon from 1913, also owned by Hagemann, but not bequeathed to the Museum Folkwang until the early nineteen-thirties. Hagemann, who was born in Essen but lived in Frankfurt am Main, acquired the painting from Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler in Paris. It is possible that the young Peiffer Watenphul’s first museum exhibition was agreed upon at this meeting in Essen after Christmas of 1920 with Gosebruch, and likely also Hagemann as well. The exhibition then took place in 1921 at the house recently donated by Dr. Hans Goldschmidt for use by the Städtisches Kunstmuseum in Essen. In 1919, Dr. Hans Goldschmidt gave his villa on Bismarckstrasse to the city of Essen for the spatial expansion of the city’s art collection. After the acquisition of Karl Ernst Osthaus’ Folkwang collection in 1922, the two villas were linked by a large addition and built together into the Museum Folkwang, which opened in 1929. No documents have survived regarding Peiffer Watenphul’s Essen exhibition in 1921. The catalogue raisonné identifies the Still Life with Grapes and Pearfrom 1921 (cat. no. G 22) as a work shown at the time, illustrated in “Der Querschnitt durch 1921.” Marginalien der Galerie Flechtheim(Berlin, Düsseldorf, and Frankfurt am Main, 1922), p. 135, Still Life(oil). The exhibition at the Kunstmuseum was accompanied by the 1921 acquisition of the painting Landscape with Woman, Landscape with Woman, 1921 (cat. no. G 24), acquired by Ernst Gosebruch in 1921 for the Städtisches Kunstmuseum Essen, confiscated on August 25, 1937, and missing since then. The 1929 catalogue of the Museum Folkwang Essen, Moderne Kunst,vol. 1, lists the following works, all of which were confiscated on August 25, 1937: Still Life,1925, oil on canvas (cat. no. G 79), acquired 1926; Women Strolling,1920, watercolor (cat. no. A 52); Woman Bearing a Jug on Her Shoulder,1919/20, woodcut (cat. no. D 2); Young Horsewoman,1920, etching (cat. no. D 3); Tête d’or,1920, lithograph (cat. no. D 4); Seated Girl,1920, drypoint etching (cat. no. D 5); Girl Filling an Amphora,1920, etching (cat. no. D 8); Woman Smelling a Flower,1920, drypoint etching (cat. no. D 9). the artist’s first sale to a public collection.

In truth, Peiffer Watenphul’s time at the Bauhaus in Weimar can only be termed an “unofficial study visit.” This is in spite of the fact that he successfully completed the preliminary course under Itten, sat in on a variety of workshops, including the pottery and weaving workshops, A slit tapestry has survived, reproduced as a color plate in Das frühe Bauhaus und Johannes Itten,exh. cat. Kunstsammlungen zu Weimar, Bauhaus-Museum (Weimar, 1994), p. 245, cat. no. 356, Bauhaus-Archiv, Berlin. and embarked on an intensive interest in the medium of photography, which would bear artistic fruit during his stay at the Villa Massimo in Rome in the early nineteen-thirties. See Max Peiffer Watenphul. Ein Maler fotografiert Italien 1927 bis 1934,exh. cat. Bauhaus-Archiv (Berlin, 1999). The leadership of the Bauhaus accorded the doctor of laws a special status among the institute’s many young students. Peiffer Watenphul was allowed to take part in all activities and, in addition, enjoyed the privilege of living in his own studio. This explains why the teachings of the Bauhaus had relatively little effect on the artist’s early work, recognized by Alfred Flechtheim to be exceptional, and which prompted him to bind the artist to his gallery by contract early on. Peiffer Watenphul’s social ties to then-prominent collectors, poets, aesthetes, and personalities between Berlin, Düsseldorf, Munich, Rome, and Paris also bespeak someone who was no ordinary Bauhaus student, but rather a young intellectual familiar with the atmosphere of artistic awakening and the company of the Bauhaus’ first masters. This impression is confirmed by another letter to Maria Cyrenius in Salzburg from Easter 1922, this time from the artist’s home in Hattingen. “Dearest Maria,” the letter begins, “I actually wanted to go to Weimar the day after tomorrow. But now I do not want to go until the Tuesday after Easter…. Here I also have such quiet to work in that I will make at least as much progress as I would in Weimar. Gosebruch was here yesterday and very taken by my new things…. He is coming again next week and bringing others with him. Either With, Contrary to Peiffer Watenphul’s belief, Dr. Karl With was an art historian for Asian art, and was active in this field for, among others, Karl Ernst Osthaus at the Folkwang in Hagen. who is the head of the Folkwang, or Jawlensky, who is in Essen and has an exhibition there. The Alexej von Jawlensky exhibition tour organized by Galka Scheyer (which ran from June 1920 until the end of 1922) made a stop at the Städtisches Kunstmuseum Essen from January 22, 1922 until February of 1922. See Mario-Andreas von Lüttichau, “Alexej von Jawlenskys Werke in privaten und öffentlichen Sammlungen und ihr Schicksal in der NS-Zeit in Deutschland,” in Alexej von Jawlensky, Reisen Freunde Wandlungen,ed. Tayfun Belgin, exh. cat. Museum am Ostwall (Dortmund, 1998), pp. 82—83. I am very glad to see how my artistic reputation is solidifying. Lately, the Ruhmeshalle in Barmen also bought a painting of mine. The painting in question is Room of H. G.,1921 (cat. no. G 23), missing since World War II. Today, Kielmansegg Wilhelm Graf Kielmansegg was for a short time editor of the journal Der Querschnitt,conceived as the continuation of the exhibition catalogues. is coming over. I have been in Elberfeld many times with Klaus, who moved me. He said it’s so modern to associate with me now…. Salmony is back from Paris and is said to have brought a great deal of material back with him, which would interest me very much…. I am only painting people, and am playing the piano a great deal: Haydn, Mozart, Debussy. Am reading Claudius, Fleming, magnificent …” Quoted in Werkverzeichnis,vol. 2 (see note 21), p. 18.

Alongside his desire to travel through Italy, the “young” artist felt it important to establish himself in the art and gallery landscape. Following his inclinations as a man of the world, Peiffer Watenphul initially oriented himself to Düsseldorf, and then, via Flechtheim’s contacts, to Paris and Wilhelm Uhde. Uhde, who had lived in Paris since 1904, had been Rousseau’s great admirer while Rousseau was still alive—indeed his discoverer, collector, and patron, along with Robert Delaunay, later the executor of Rousseau’s estate and the promoter of his popularity in Germany within the circles of Der Blaue Reiter. Uhde was also a valued partner and adviser for Flechtheim with regard to French and German artists alike who resided in Paris and gathered at places like the Café du Dôme. The Café du Dôme was a meeting place for artists at the intersection of the Boulevard Montparnasse and Rue Delambre. These included Rudolf Levy, Hans Purrmann, Jule Pascin, Ernesto de Fiori, Karli Sohn-Rethel, and others, some of whom Peiffer Watenphul became acquainted with before the end of World War I and with whom he enjoyed lifelong friendships.

Uhde also introduced Flechtheim to Kahnweiler, who sparked Flechtheim’s initial enthusiasms as a collector of contemporary French art, in particular, for Derain the “Fauve,” the Cubists Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, and for Fernand Léger and Juan Gris. Thanks to his intensive assistance for the expansion of Flechtheim’s gallery plans after World War I, initially in Düsseldorf and then in Frankfurt am Main and Berlin, Kahnweiler assumed, in his role as an intermediary and through Flechtheim’s monopoly power, lasting influence over the dissemination of French art in German private collections. See Stephan von Wiese, “Der Kunsthändler als überzeugungstäter, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler und Alfred Flechtheim,” in Alfred Flechtheim 1987 (see note 10), pp. 45ff. This is hardly to say that Flechtheim neglected his work as a patron of young art. At his gallery, he placed the artists of Das Junge Rheinland Among the most important artists of Das Junge Rheinland were Otto Pankok, Gert Wollheim, Hans Rilke, Karl Schwesig, Adalbert Trillhase, Theo Champion, Heinrich Maria Davringhausen, Bruno Goller, Adolf Uzarski, Max Ernst, Otto Dix, Conrad Felixmüller, and Paul Klee, as well as littérateurs and journalists including Dornseif, Hannes Küppers, and Gert Schreiner. (as they had called themselves since 1919) in context with international, primarily French painters. The members of Das Junge Rheinland did not fully establish themselves, however, until they were aided by the brilliant Johanna Ey, who built her coffee shop and art gallery into the center of the movement and, with the polemical journal Das Ey , achieved widespread notice that brought her and her friends into contact with other centers of young art in Munich, Dresden, Hanover, Weimar, Berlin, and elsewhere. Through Flechtheim, Peiffer Watenphul joined the circle of these more or less established artists of Das Junge Rheinland, then in the midst of their first important development, and who found affirmation and support in this loose association. On the history of Das Junge Rheinland, see Ulrich Krempel, “Am Anfang: Das Junge Rheinland,” in Am Anfang: Das Junge Rheinland. Zur Kunst und Zeitgeschichte einer Region 1918–1945,exh. cat. Kunsthalle Düsseldorf (Düsseldorf, 1988), pp. 8ff. Peiffer Watenphul’s relationship with the Düsseldorf scene and Johanna Ey was an enduring one, despite the many discussions regarding political values and reforms in the art scene and at the Düsseldorf art academy in the nineteen-twenties. Their relationship deepened while he taught at the Folkwang Academy in Essen from 1927 until the coming of National Socialism in 1933. Peiffer Watenphul photographed Johanna Ey ca. 1930/31 and again in 1934. See Werkverzeichnis,vol. 2 (see note 21), cat. nos. P. 50, 51. He participated in exhibitions together with Das Junge Rheinland in: 1921 (February 27 — March 29, 2 paintings, 1 watercolor, 1 etching: Girl Filling an Amphora, 1920, cat. no. D 8, illustrated in Der Querschnitt,vol. 2/3, May 1921, p. 911), 1923, 1927, and 1931. One of Peiffer Watenphul’s earliest attested exhibitions was also mounted at Flechtheim’s gallery in Düsseldorf, from mid-October to mid-November 1921. Exhibition at the Galerie Flechtheim, Düsseldorf, October 15 — November 15, 1921. According to the catalogue raisonné, the works on display there included the following, among others: Landscape,1920 (cat. no. G 8), Still Life,1920 (cat. no. G. 11), and The Artist’s Mother in Profile,1921 (cat. no. G 26).

After returning from his first extended trip to Italy in the winter of 1921 and 1922, on which Peiffer Watenphul went to Positano via Rome and Naples, he stayed for some time in Salzburg, there to work with Maria Cyrenius in her enamel workshop and to pursue a renewal of enamel painting. Salzburg, like Venice, was a city that held a perpetual fascination for Peiffer Watenphul. In addition to his visits with his good friend Maria Cyrenius in Salzburg, Peiffer Watenphul began teaching at the School of Arts and Crafts in Salzburg in 1943, following his departure from the textile school in Krefeld, and remained there until early 1946. In 1964, he took over the leadership of the Summer Academy of Fine Arts in Salzburg from Oskar Kokoschka and served for five years in that capacity. Until his journey to Latin America in July 1924, Peiffer Watenphul commuted between Weimar, where he maintained a residence until the end of 1923, Düsseldorf, where he rented a large studio in January of 1923 that cost him “a lot of heating,” and his home town of Hattingen. “For now, everything is just provisional,” he reported to Maria Cyrenius in Salzburg. His hope to establish an enamel workshop at the School for Artisans and Arts and Crafts in Essen was not to be realized then, nor was his hope to teach at that important emerging educational institution. The times proved increasingly unfavorable for the visual arts, and it remained a challenge to establish a school based on Karl Ernst Osthaus’s Folkwang concept.

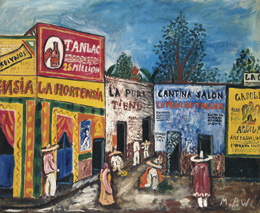

Without further reasons to stay in Germany, Peiffer Watenphul resolved to travel to Mexico in July 1924. There, his painting changed decisively under the influence of the country, the climate, the landscape, and the fauna. His use of color became more aggressive, the style of the brushwork much more powerful, nearly Expressionist, and the paintings’ subjects “tropical.” As Peiffer Watenphul related to Maria Cyrenius: “I think that in Germany they expect jungle paintings from me in the style of Rousseau. They will surely be very disappointed, since here I see everything very differently. Colorful, half-kitschy, and yet so infinitely appealing.” See Werkverzeichnis,vol. 2 (see note 21), p. 24. Among other things, he was also “busy painting decorations for the German festival, the people of the small town of Kotzebue … scenery measuring 9 x 7 meters. I had to paint that all by myself, squatting on the ground.” Ibid., pp. 20–21.

This transformation in Peiffer Watenphul’s style could hardly have been clearer, and it represented, alongside its site-specific aspects, the fundamentally striking characteristic of the Mexican paintings. Back in Europe, in the spring of 1925, Peiffer Watenphul turned back to the style of his Weimar period, his Mexican enthusiasm for color gradually fading away. In uniting different temperaments, he initially created a multitude of still lifes, the things depicted powerfully pronounced yet familiarly mannered in how they were drawn, as well as a small number of landscapes, based primarily on the artist’s extended travels in the South, to Yugoslavia, Italy, and France.

Before the formal establishment of the two Folkwang schools in July 1927 and February 1928, Max Peiffer Watenphul was commissioned by the architect Alfred Fischer, then the Folkwang’s director, to assume responsibility for the disciplines of design, enamel, and embroidery, and later, also the crucial preparatory courses at the School for Artisans and Arts and Crafts, entirely in keeping with the style of the Bauhaus and its claim of total education. Peiffer Watenphul was outstandingly fit for his position, one assessment suggested, because he could “familiarize students with the general means of artistic design through a clearly constructed, systematic pedagogical program, and knows how to teach the fundaments of forms and color.” Dr. Käthe Klein, Aus der Geschichte der Folkwangschule für Gestaltung(Essen, 1965), p. 30. Shortly before this time, the Bauhaus graduate Max Buchartz had come to Essen to take over the division for advertising graphic art and photography, and in 1928, Grete Willers, also a Bauhaus student, took over the division for embroidery and weaving. Old friends from the Weimar years came together again in Essen, this time on the other side of the lectern. Peiffer Watenphul made the acquaintance of other masters in Essen, including the sculptor Joseph Enseling, head of the class for sculpture, and the painter Karl Rössing, who was in charge of the teaching of book art. Rössing would also be Peiffer Watenphul’s contemporary at the Villa Massimo in Rome.

The artist’s teaching position at the Folkwang schools endowed him with a new measure of independence. With financial security, he gained the opportunity to travel broadly, including to Berlin, Monte Carlo, Paris, London, Venice, Morocco, and time and again to Rome. “From Monday to Tuesday I must be in my studio space from eight until two, and go over to the class twice to make corrections. Am receiving 430 marks. So one can speak of a mad joy,” Peiffer Watenphul wrote to Maria Cyrenius in Salzburg. This paradisiacal period lasted nearly four years. In 1931, Peiffer Watenphul was awarded the prestigious Prize of Rome, linked to a nine-month residency at the Prussian Academy of Arts in the Villa Massimo. In Rome, his long-term future as an artist and his personal environs were decided. Max Peiffer Watenphul, molded by the Ruhr region, molded by the Weimar Bauhaus and the Folkwang schools in Essen, had now arrived in his beloved Italy.

In: Max Peiffer Watenphul und Italien,exh. cat. for the eponymous exhibition at the Museo Nazionale di Castel Sant’Angelo (Rome, 2000); Edizioni de Luca, 2000.

© Dr. Mario-Andreas von Lüttichau.

Reprinted by kind permission of the author.