Ulrich Krempel

A Matter of the Heart: Max Peiffer Watenphul and Italy

Italy was an obligatory experience for every German artist in the nineteenth century. It was the realm in which to encounter classical antiquity, the art of the Renaissance and the Baroque. In the nineteenth century, young artists made pilgrimages to Italy to train themselves from the sublime examples of the great figures of the past. By contrast, for twentieth-century German artists, the given artist’s own choices revealed the country and its culture. Those who traveled from Germany to Italy in the twentieth century—and, in particular, at the beginning of the century—often still followed the academic canon, heeding the young artist’s duty to make the “Grand Tour,” the educational journey to the foundational sites of Western art. Perhaps, it was still clear to such travelers the great extent to which they stood in the tradition of those German artists and historians who, for example, as “German-Romans”, had joined their own lives and biographies to Italy, its artistic landscapes and its great cities. Apart from being an academic tradition for the artists of Romanticism and the Wilhelminian Neorenaissance, not only was Italy the living rebuttal to German political sectionalism, German narrowness and provinciality, and the dismal German climate and mood, but Italy was also an opposing world, with atmosphere and broad landscapes, with light and sun. Above all, the German artists who traveled to Italy in the twentieth century were those in search of “the South” and the impetuses it provided for subject matter—light and color from reality for use in painting.

Travel was both an elixir of life and the basis of professional life for the young German painter Max Peiffer Watenphul, and, indeed, for other painters like him who depicted atmosphere and light, nature and landscape, and the experience of space and perspectival distance in their work. His travels within Europe, to Austria, France, and England, and even to Mexico attest to the young painter’s hunger to see the unseen and become acquainted with distant cultures and the suns and landscapes of other continents. The most intense of all the artist’s links to life outside Germany, however, was his encounter with Italy, which began in 1921 and, on many levels, influenced his entire life thereafter. The young painter traveled to Italy for the first time in the autumn of 1921, staying until the spring of 1922. He visited Rome, Naples, and Positano, where he met his friends, the artists Karli Sohn-Rethel and Werner Heuser. January of 1922 he spent in Rome. In August of 1925, he went with Maria Cyrenius, an artist friend from Salzburg, to the city of Ragusa (Dubrovnik), extremely similar in mood to Italy. The painter traveled again to Italy, namely, Florence, Venice, and Rome while an instructor at the Folkwangschule (from 1927 until 1931). In 1931, he was awarded the prestigious Prize of Rome and returned to that city, where he lived to do his work alone for nine carefree months. In the summer of 1932, he went to Gaeta for a month with his sister Grace and the couple Karl and Erika Rössing. The painter did not return to Rome until the autumn of 1933, remaining there until May of 1934.

Villa Massimo

“So I have four rooms plus studio and terrace. Everything magnificent. The park is an exceptionally elegant, old affair, with old sculptures, cypresses etc. Everything very great, ten people are here. Everyone very nice … Will begin painting tomorrow … On Monday, we all took an excursion to the Etruscan cities of Norma and Cori, high in the mountains. Also magnificent. A view all the way to Naples. For the last week, we have had the most magnificent radiant summer weather you can imagine. The air is full of birdsong and everything is growing green and the flowers are blooming. Perfect, in other words. What is more, I have already gotten to know a lot of people…. Freedom is so magnificently beautiful. No one says anything to you. I am enjoying every hour—for it will never be this way again. Hopefully, I’ll make some progress here with my work. For now, I’ll just take things in, and devote myself entirely to that.” Max Peiffer Watenphul, letter to Maria Cyrenius, autumn 1931, in Max Peiffer Watenphul. Werkverzeichnis,vol. 1, Grace Watenphul Pasqualucci and Alessandra Pasqualucci, eds. (Cologne, 1989), pp. 28–29.

The unbounded freedom to look around and to live out one’s own work entirely—how liberating a prelude to the theme of Italy in the work of Peiffer Watenphul, the painter. And yet—perhaps exactly in view of these great new opportunities—the beginning was hesitant and still lacked the clear intensity of his later Italian works. The painter built his Roman stages cautiously. They all share a quiet “viewishness,” bound into a rigid framework of verticals and horizontals. The painter directs our gaze into a tightly hierarchized visual space, in which trees and shrubbery provide verticals from nature; against these, walls and pedestals, plinths and columns, vases and houses represent the works of man, the artistically formative element of this new lived environment. Many of these architectural elements rise up vertically while the horizontals of the terraces, balustrades, and walls organize the base for this element of built aspiration.

These views are almost always devoid of people. The human figure is only present through the indirection of sculpture in the painter’s first paintings of Rome. In all of these urban park landscapes, sculptures, busts, and torsi are the measure of human presence. The paintings are unmoving, statuesque, like frozen scenes out of long, quiet processes of artistic observation. Because the paintings are a carefully constructed result of the artist’s outlook on reality, the painter gives his viewers occasion to gain their own outlook on the scene, the nature and the mood gathered in the painting. The human presence through the indirection of its formulation through classical sculpture becomes the painter’s artifice. He communicates the experience of his arrival in the great theme of Italy: Everything has its measure in these paintings, and the human figure even has the classical measure, according the highest criterion to the artist. This is both a playful presentation of the human presence as well as the identification of the highest criteria within the artistic horizon of the artist’s work.

These Roman views of the early nineteen-thirties also avoid the glowing intensity of color and light in Peiffer Watenphul’s later paintings of Italy. In Rome, Park Landscape I, and Park Landscape II , both from 1932, the scene is composed from the simultaneity of earthy umbra tones, sharply defined clear white areas on marble and tree trunks, and the green tones of vegetation leaping out into the leaves, appearing strangely cold and devoid of vitality in the bright Italian light. The sun is high in the painting, as can be seen in the few short shadows; the skies play into gray, into the bluish glass of the bright midday. The scene’s cool layout corresponds to the precise illuminating light and the emotional contrasts of color; the scene is made empty intentionally, cold and precise. A German observer may be reminded of New Objectivity painting, although this has been subjected to a painterly breaking. In a passage from a letter, the painter himself observed that the intention of his style corresponded to an original Italian contemporary, namely Giorgio de Chirico. Thus, the artist wrote in 1934: “Also naturally painted a great deal, but only now am I really getting the hang of it. Still lifes with classical motifs that are so appealing, but also difficult, since there Chirico has anticipated everything. And yet, I would really like to create something new there. I also believe that I am on the right path now …” Max Peiffer Watenphul, letter to Maria Cyrenius, February 1934, in Werkverzeichnis,vol. 1, p. 34.

private collection

During these years, the bright overall organization of the painting is occasionally reversed into its exact opposite. In the painting Villa Massimo in Rome from 1934, the brightness of the paintings discussed above yields to the new scene’s darkness. Trees and plants stand darkly in a darkened space; the sky is overcast with dark clouds, but over everything there is a soft white light, perhaps emanating from the bright moon apparently shining outside the image. In Villa Massimo in Rome , the opposites of light and dark construct spatialities of the sort we know from Peiffer Watenphul’s later paintings: Differences in the brightness of the colors in the paintings cause volumes and spaces to arise in the image.

Arising on the stages of the early Roman paintings is the young painter’s first great avowal of this country, to its light and its nature. His letters overflow with ardor for the great love of his life, Italy, which he first expressed in a letter to his friend Maria Cyrenius in Salzburg in April of 1932: “The days fly past. In Frascati, after visiting the villas, we had a delightful picnic outdoors amidst almond blossoms and peaches. Now the roses are coming, roses entwined around everything in torrents. The wisteria is already in bloom. I love Italy more than I can say, and it is tragic that I cannot live here. Am painting old terraces and ruins with statues in between. Trees with dark foliage…. I will try to stay here as long as possible. In July I wish to go to Capri, where things are said to be cheap and one can paint and swim.” Max Peiffer Watenphul, letter to Maria Cyrenius, April 1932, in Werkverzeichnis,vol. 1, p. 31.

In the South

Peiffer Watenphul was not the only German painter in Italy in those years. In Rome, he saw Werner Gilles, whom he knew from Düsseldorf, and encountered Rudolf Levy (later murdered by the Nazis), the director of the Villa Romana in Florence, Hans Purrmann, Eduard Bargheer, Kurt Craemer, and Emy Roeder. To all of them, the landscape, light, and color in Italy embodied what was unattainable in Germany. German painters, in contrast to French artists, for example, had no South in their own country, the South that had made possible such categorically different works. In addition, the transfer of power to the National Socialists had radically altered the artistic situation in Germany. These individualists and loners hoped to continue working, and survive the political confusions of the age unscathed in Italy.

The marriage of Peiffer Watenphul’s sister Grace gave him occasion for private reasons to travel to Italy. In March of 1936, he was again able to leave Germany; he stayed first with his sister in Latina, then went to Sorrento, Capri, and Ischia, where he remained for an extended period. In November and December, he continued on to Sicily, and visited Palermo, Catania, and Agrigent. Back in Germany, the evidence accumulated that the artist was being kept under surveillance. Plans to emigrate to England or France did not come to fruition. In the autumn of 1937, the artist received, with the aid of his sister, a residency permit for Italy. While he was in the process of leaving Germany, his paintings were confiscated from museums in Berlin, Essen, Cologne, Mannheim, and other Germany cities as part of the “Degenerate Art” campaign; his flower painting that had hung in Berlin was defamed through inclusion in the Munich exhibition of “Degenerate Art.” It was impossible thereafter for the artist to exhibit his work in Germany. In December of 1937, Peiffer Watenphul went to Ischia, to the island he had already come to love the year before.

“Here, it is very beautiful. I ran into Gilles, who is here. The weather is unfortunately very cool, and swimming out of the question. I would like to paint, but do not have the quiet to do so, in spite of how much appeal the area has for me. The many small bays. The great, gloomy pineta, the circular harbor, the sailboats, the houses that are limed white and pink. These are actually all finished pictures already. But I do not want to paint them up ‘frivolously.’ And to shape it, one needs time.” Max Peiffer Watenphul, letter to Maria Cyrenius, Ischia, March 1936, in Werkverzeichnis,vol. 1, p. 36.

What the painter described in this 1936 letter to Maria Cyrenius became, in the years that followed, and alongside such themes as the flower still lifes, a flood of paintings full of compositional power and intense color. He was now working continuously on the island, interrupted only by short travels to Cefalù, and to visit his sister in Latina. Artist friends from Germany came together on the island, including Gilles, Levy, Bargheer, and the composer Gottfried von Einem.

This was, all told, a happy time for Peiffer Watenphul, in which he attained a new painterly intensity in his shaping of the Italian landscape. Inspired by the breadth of the sea, the paintings expanded in spatial dimensions. In Ischia from 1936, for example, the painter conquered the pictorial space in swift steps. The entry into the open landscape is dynamized by the truncation of the bushes and flowers in the left foreground; with the next step, we are already in the middle ground of the image, among the houses on the seashore; the view over the sea is impeded on the mountainous opposing shore, and runs out at last in the cloudy sky above it. The foreground, middle ground, and background are equal in intensity and presence in the eye of the observer because the painter has structured the scene in so balanced a fashion. The objects in the image are increasingly identified with painted and drawn abbreviations, and the characteristic style of the brushwork gains in formative power to depict the atmospheric qualities of land and sea. In Cefalù from 1937, there is, again, a sky high above, sweeping out far beyond the observer to span earth and water. In the painting’s foreground, vegetation, near and far, blocks the view into the depth of the space. Laterally displaced from the center of the image is a view of the city and sea, and at the right edge of the image on the high-jutting mountain. The mountain and the trees rise the same height over the dominant horizontal of the horizon; in this way, the foreground and the middle ground are drawn together and interwoven in the composition. Peiffer Watenphul channels our gaze into his paintings of these years. In the paintings’ composition, he paints paths for our sight into the landscapes, corridors along which our gaze is led. To the viewers, the painter makes a gift of lofty angles and elevated points of view in these paintings, these overviews and insights constructed through the convincing and compelling reduction of object and composition.

Venice

“In 1941 the war forced me to return to Germany. At that time, I was offered a position at the textile school in Krefeld. There was such a shortage of men that recourse was made even to the ‘Degenerates.’ There, I took over the class for graphic design. I found the work wonderful, and it might really have been perfect…. Then, there were the dreadful bombing raids. When my studio and all its contents were destroyed, I terminated my contract, which had two years left and departed disagreeable Krefeld for Salzburg, where, in prior years I had run the enamel workshop with Maria Cyrenius. The years in Salzburg were lovely. I worked immensely and had great success there, including official purchases by the Albertina, etc. It was, in other words, a good period. After the war ended, however, it was remembered that I had German papers, and the abuse by the authorities began…. Since I had no relationships with Germany and had not lived there in so many years, I did not want to go back. Instead, I came here, where my mother and my relatives live.

Unfortunately I had hardly come into the house out of the rain before I found that a man, when he is German, is treated as a pariah.” Max Peiffer Watenphul, letter to Johannes Itten dated January 27, 1947, in Max Peiffer Watenphul,exh. cat. Wuppertal (1991), p. 85.

What Max Peiffer Watenphul wrote in January of 1947 to his old teacher Johannes Itten is a laconic summary of the previous six years of his life, following his return to Germany in 1941. With no passport after the war’s end, he went from Austria to Italy on foot by night. The painter was once again in Italy, back with his family, but had neither the slightest means to get by nor possibilities to exhibit or sell his work. His new living situation in the middle of the lagoon city of Venice, without the far horizons of the South, also made work difficult. It was not until April 17 of that year that he was able to write to his friend Maria Cyrenius in Vienna: “Yesterday I finally painted my first painting of Venice that pleases me to some extent.” Max Peiffer Watenphul to Maria Cyrenius, dated April 17, 1947, in Werkverzeichnis,vol. 1, p. 48. And he wrote her again on May 15, 1947: “I regard everything with feelings of bitterness when I think of people who are dear to me and who lack everything. The world is mad. For weeks I have been painting pictures of Venice that are now starting to get very good. But first I had to work my way up to it. Earlier I painted landscapes, now architecture, water, people.” Max Peiffer Watenphul to Maria Cyrenius, dated May 15, 1947, in Werkverzeichnis,vol. 1, p. 49. In November of 1947, the painter wrote Wolfgang Bingel, recounting his ongoing struggle to attain a new way of seeing the old theme of Venice: “I exert myself in every brushstroke to paint it as well as I can, and as laden with sensitivity as I can. If I see that a stroke is not those things, I scratch it off. This is how I work through my paintings centimeter by centimeter, and no empty areas are permitted. The extent to which I am tormenting myself here with my new paintings in Venice I cannot begin to tell you. I am really working like a madman.” Max Peiffer Watenphul, letter to Wolfgang Bingel dated November 11, 1947, in Werkverzeichnis,vol. 2, p. 34.

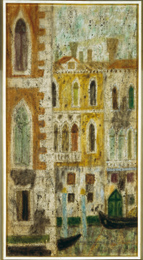

Venice, Ca d’Oro from 1947 is one of the first genuine expressions of the artist’s efforts to find a new side to the exceedingly well-known and exhausted image of Venice. The painting draws on the kind of depictions of landscapes that the painter had developed in the South fifteen years earlier. An optical repoussoir in the foreground is the window frame or shutter in the left third of the canvas, beyond which is the view of the Canal Grande, the gondolas, two palazzi , and the adjoining piazza. The picture is tightly limited in its framing, with the horizon line of the houses pressing almost up to the canvas’ upper edge. The image is thus comprised of a foreground at left so strongly truncated that no details may be derived from it, a middle ground of the canal with ships overseen toward the rear, and a background of the scenery of the two palazzi’s façades. The sky has the effect of concluding upward, affirming exterior space as though by reference to the artist’s earlier landscapes.

The artist worked with a comparable pictorial construction in other works of his early period in Venice, as in Venice, Canal Grande from 1948. In this somewhat later painting, the view is pointed at the Canal Grande, running rearward. The repoussoir of the open window is now located on the right side of the image. To the left, in the near middle ground, are the strongly truncated façades of houses that mark off a corner of the canal. From there, our eye springs across the canal, which flows into the painting from the rear like a street, to the opposing fronts of the palazzi , and our eye falls, after another bend of the canal imaginable in the background, onto a narrow strip of palazzo that concludes the image at the back in the lower half of the canvas. An amorphous cloud formation hangs over the palazzo here, making the sky more clearly perceptible than in the work discussed above. Yet, this painting again presents the peculiar technique of spatial construction that, like constructing stage scenery, carefully directs our eye and introduces built paths into the painting.

The painter’s decision in favor of such a carefully calculated, strictly built design for Venice, opening itself into stage spaces, was an entirely conscious one. In 1952, the artist as author spoke to the subject of a “A New Venice”: “It is monstrously difficult to find new painterly facets of Venice. Everything is photographed and illustrated on postcards with such unbelievable frequency that one really dreads seeing again and again the usual vedute of San Giorgio, of the Piazza, or the Rialto. I exerted myself for a whole, long year, and each evening, repeatedly destroyed what I had painted in any given day because I just could not seem to succeed in seeing anew, and providing a personal tint to my depiction of all these so unbelievably frequently illustrated things.

Venice is a city that has two entirely contrary and different faces. Jean Cocteau said to me at my exhibition: ‘Theater is always being played out in Venice. This is a city in which the street is the stage and the windows, the boxes full of spectators! Once, while dining at the Ristorante Fenice, I was served flaming Crèpes Suzette, and all the spectators in the windows began to applaud and call out ‘Bravo!’ just like a great scene in the theater.’” Max Peiffer Watenphul, “Ein neues Venedig,” text dated January 31, 1952, quoted in Max Peiffer Watenphul,exh. cat. Wuppertal (1991), pp. 89–90.

Stage structures of this kind, namely gazes organized by the artist into peep show-like pictorial spaces, dominate the new views of Venice, just as the artist sought to organize these gazes through great exertions. Our lines of sight are those of spectators seated in theater boxes, with the boxes’ limitations on the pictorial field occasionally still perceptible in the view into the painting. Unfolded before us is an image of a city thoroughly devoid of people, with only the occasional figures visible in the gondolas. In these paintings, Peiffer Watenphul captures the experience of life in the city of Venice across the entirety of the year. In both paintings and texts, he often emphasized the difference between the lively summer theater of Venice and the melancholy winter moods in which, between wealthy residents departing and tourists staying away, the city was nearly deserted. “Venice is the city of light. It takes form through light. Without the sun, it collapses and is disenchanted. Light gives life to its façades and makes the cupolas of San Marco resplendent. Venice is most beautiful in the autumn and in the spring before dusk.

Everything glitters like mother of pearl and is delicately iridescent. People flood suddenly over the rolling bridges and the piazza, everything is lively and breezy. Blue and gold fog gently veils the city, and above the fog, the departing sun gilds the Campanile and the cupolas of San Marco.” Max Peiffer Watenphul, “Gedanken über Venedig,” dated January 1952, quoted in Max Peiffer Watenphul,exh. cat. Wuppertal (1991), p. 91.

The delicate colors and the painterly sfumato , the attempt to thus capture the atmosphere and the high humidity, the delicate fog, and the play of light repeatedly characterize Peiffer Watenphul’s early painterly solutions to views of Venice. In Venice, Ca’ Foscari from 1949, a light pink dominates the entire view, strictly constructed and traditional. The landscape-format organization of the canvas is particularly structured toward the water and the sky; the view of the palazzo , slightly shifted toward the center, makes these into an essential medium for the vertical tectonics of the pictorial construction on the whole. Here again, the artist works repeatedly with the motif of blocking lines of sight so as to organize a painting’s view in a certain fashion. For example, he incorporates a wholly amorphous spatial building at the right edge of our painting without the slightest formulation of detail, so as to focus on side canals in the gap and, at the same time, to use contrast to emphasize the real central theme of the painting. Peiffer Watenphul does not, however, shy away from using the commonest and most conventional elements associated with views of Venice, such as the constantly present gondolas with shadowy figures, who seem like staffage elements rather than actually identifiable figures. The gondolas are set pieces for the depiction of distance. They attest to the presence of water and make perceptible what is specific to this city. Yet, large rowboats and ugly merchant ships can also be found in these paintings. As in the landscapes of the South and in the early paintings of Rome, Peiffer Watenphul endows his views with a peculiar timelessness. Nothing is really characteristic of a particular time, and this Venice looks at us agelessly, in a way we can still experience it today, if, like the artist, we simply look past the motorboats and the loud contemporary hubbub on the canals.

This timelessness is also aided by color. Nearly every painting of Venice has its own color tone, its own mood. It is not without cause that Peiffer Watenphul makes repeated reference to the fact that, for him, there had been no major new renderings of the Venetian theme since the city was interpreted by Claude Monet and Auguste Renoir. The painter works from these models, as well as from the great classic interpretations of Venice by William Turner and Canaletto. These are the measures that inhabit the visual memory of our artist, compelling him to arrive at a formulation entirely his own. And that formulation, in the work of Peiffer Watenphul, is a monumentalization of the individual view, in a topography related to the individual building, the individual palazzo, the individual view. It is the vision of someone seated, resting, now and then strolling, who on reflection, selects the views that he captures first as drawings and later as paintings. Venice is always present as environment, in its individual moods and in its views of extremely reduced nature; and these appear like scenes of a stage piece in the Venetian theater of Max Peiffer Watenphul.

Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich

© Blauel/Gnamm — ARTOTHEK

The artist lived in the utmost isolation during these years. Recognition did not come until one of his paintings was shown at the Venice Biennale in 1948. Two years later, at the XXV Biennale, Peiffer Watenphul was finally presented together with Max Beckmann, Karl Hofer, Georg Meistermann, Ernst Wilhelm Nay, Emil Nolde, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Fritz Winter, and others in an overview of contemporary West German art. Eberhard Hanfstaengl, curator of the German Pavilion, placed Peiffer Watenphul in the proximity of his contemporaries. One of the works exhibited here was Venice from 1950, a classic, close-up composition of the front of a house in Venice, seen across a dark canal and caught in the strict tectonics of a palazzo architecture barely defined in the left third of the canvas, then exquisitely built up in the two thirds to the right.

Almost the entire breadth of the painting’s foreground is occupied by a gondola with a tent on it. The gondolier stands on the stern of the little boat and indicates the powerful movement of rowing in which the artist has captured him. In the intensity of the statue-like form and stillness of the image, the moment of stopped movement is the only dynamic moment to ultimately enable a dissolution through movement of the stasis of the structure of the dark earth tones and the broken reds and black. Peiffer Watenphul himself had already referred to this darkness of Venice in his texts on the city, describing it as a “composition in black and white without color of any kind.” Max Peiffer Watenphul, “Ein neues Venedig,” (see note 9).

Max Peiffer Watenphul’s twelve Venetian years display great insistency in his treatment of the theme of Venice. The variations of the views range from extreme landscape formats to steep portrait formats, paintings in which the limitation of clear views in the lagoon city and the orientation toward the skyward-striving tall houses reflect one another. One such extremely ascendant portrait format, in the painting Venetian Palazzo from 1958, represents not only the pictorial medium but also, to some extent, a repetition of the theme of extreme ascent. In the left third of the canvas, we behold a house façade rising up three stories, reproduced in a narrow excerpt; our eyes move past this to the docking posts rising up in the canal, and then behind them, two palazzi strive heavenward, each three stories tall and with chimneys clearly visible on the roof. The vertical organization, repeatedly interrupted by the subdividing of the buildings into floors, endows the pictorial construction on the whole with rhythm. Legible in the house façades is a play with the measure of three and the façades’ shifting toward one another; through the perspectival alignment in the background, this measure of three is joined by a measure of five, with water and sky legible to an extent as units of their own. Extreme portrait formats and extreme landscape formats alike became interestingly passable paths for Peiffer Watenphul during the late nineteen-fifties, with extreme portrait formats for the city views of Venice, and extreme landscape formats for landscapes, in particular, those that look down onto a seacoast from land at a height. Thus, the painter stages panoramic views or their refusal; the pictorial format itself suggests to the observer the place that both the painter and observer must imbibe to understand the scene presented. Peiffer Watenphul used his twelve years in Venice to immerse himself intensely in the theme that he depicted. The slight variations of themes over so long a time bespeak a great intensity in approaching the depiction of this so specific a city. In many of these views, a merriment can be sensed that the painter was not able to feel in Venice at the beginning of his years there. Melancholy, atmosphere, and light mist, in the ever more graphically conceived depictions, are components that gave these paintings a particular intensity of experience for onlookers at the time and for us as observers today.

Peiffer Watenphul finally achieved success in exhibitions after he was shown at the Biennale. Carlo Cardazzo organized the painter’s first solo exhibition at his Galleria del Cavallino in Venice in August of 1948. In Germany, he was shown soon thereafter in Braunschweig and Düsseldorf. He was drawn into artist circles in Venice through contacts with Italian artists, in particular, Filippo De Pisis, Felice Carena, and Zoran Mušič. Mostly German visitors, including Ernst Gosebruch, Tut Schlemmer, Ludwig Curtius, Gertie von Hofmannsthal, Cocteau, and Stefan Andres, met with him during visits to Venice. And once again the artist traveled to the south of Italy, traveling in 1949, for example, to Rome, Naples, Caserta, Positano, and Capri, and met up on the way with artist friends, including Sohn-Rethel, Craemer, and Andres. He spent a month in Florence in 1950. In the autumn of 1951, the artist received a new passport and was at last able to travel outside of Italy. His first trip was to Salzburg, and in January of 1952, he traveled to his old homeland, to Essen, Dortmund, Wuppertal, and Braunschweig, as well as to Zurich.

Back to the South

Peiffer Watenphul’s travels in the nineteen-fifties and nineteen-sixties took him to a variety of destinations and, time and again, to the south of Italy. Ischia and Positano were places that he visited and viewed over the years. Ischia was the impetus for the painter’s great southern landscapes. Here, a turn to the extreme landscape format cannot be overlooked in his oeuvre. The specific theme of Ischia was one he conceived ever more panoramically, in wide-framed views that stretch out in breadth, like Landscape on Ischia from 1956. The individual elements of the depiction are the same within a slight range of variation. The expanse of the landscape is divided into three parts, a narrow band of earth in the lower part of the painting, the view out over the expanse of the sea in the middle part, and the lofty sky in the upper third. All subsequent portrayals are subject to all three elements, like colored ribbons in azure blue, in the deep blue of the sea, in white or brown. In front of these are the classical opposites of nature and civilization: the cypresses and pines, soaring elements of classical simplicity, and against them, the cubes of the houses, assembled from curves and simple tectonics. This broad-format composition is carefully weighed, balanced, and intended for viewing; it offers a harmonic structure of natural and constructed forms, circles and lines, rectangles and squares. The painter gained a great sureness of design in his late years in the South; the elements are defined, and variations arise through the placement of these views in various seasons. The painter now developed a particular preference for blooming flowers, blooming trees, the light additional attributes of the seasons, and the principle of eternal growing and blooming. We will find these things again in his powerful flower still lifes.

Peiffer Watenphul developed new elements in his city views of Venice that are to be found in his paintings thereafter. It is not difficult to make out a texture of draughtsman-like reworkings of the views on the whole, nervous, writing-like movements to be found time and again on the image surface. Like notations from a different and new structure of drawing, or like markings of the movements of otherwise nearly invisible things, the hot shimmering air and the atmosphere’s turbulences and movements seem held in place. Likewise, the texture of the application of paint repeatedly seems to follow references to directions, and thus, to identify its own whirring and glimmering moments of atmosphere.

Later, in 1965, the painter examined his love for the South in critical retrospect. He thought back to the once half-abandoned places where he and many other painters had stayed, now overrun with tourists. “Shortly after World War I, a group of young painters from around the world and I discovered a place on the Gulf of Salerno: Positano. It was this half-abandoned village of white, cubic houses rising precipitously from the blue shores of the Mediterranean up to the mountain sides. It was a wonderful subject matter for us painters. We painted and drew the city, exhibited our works throughout the world, and thus, helped to make Positano famous. The decaying, primitive fishing village became a famed tourist destination with large hotels. For us painters, Positano lost its peaceful appeal and we sought to find a replacement for this paradise.

Thus, we discovered Ischia, the beautiful island with the pine groves, quiet bays, and little white houses and hot springs. Again, we painted this beautiful island, exhibited our works and, again, helped to attract streams of tourists to this landscape. Large hotels were built, and a genteel life arose. Peace fled from this landscape, and once more we painters had to set forth to new shores. This time, I went alone on my journey of discovery and discovered a new paradise for myself: Corfu. Here, again, were the forests (real forests) of olive trees, overcast by gray, the violet-hued sea of Homer, and an endearing populace. Corfu is the third discovery in my life.

Will the island stay as paradisiacal and majestic as it is now? Or will I have to move on someday and make my fourth discovery?” Max Peiffer Watenphul, “Entdeckungen,” dated July 1, 1965, quoted in Werkverzeichnis,vol. 1, p. 75.

Rome in the Nineteen-fifties and Nineteen-sixties

The painter acquired a small studio in Rome, on the Via dei Greci, in the autumn of 1957. He relocated there one year later. “It was a very small but elegant apartment, with two rooms on the top floor. A tiny spiral staircase led into the little studio, which opened onto a terrace with a view of the Pincian Hill. No street noise could be heard, only the music of the nearby Accademia di Santa Cecilia. Here, he painted on a table without an easel, a practice he had already adopted in Venice. One could find him painting that way in the early morning, and by nine o’clock he had usually already finished a painting. There were agaves on the terrace in the lovely gray-blue tones to be found in his paintings. The walls were hung with works by painter friends, a collection he had assembled through exchanges with other artists over the years. His great joy was his collection of small Greek sculptures. The little kitchen had a pink tile floor, and that was where he cooked, for he was a passionate cook throughout his life. Everywhere he lived, he cooked for himself and was renowned for his recipes.” Quoted in the biography of Max Peiffer Watenphul published in Werkverzeichnis,vol. 1, p. 595. The artist’s return to Rome was also a sign of his personal success. A certain degree of success in Germany and Italy prompted him to move on from his cramped life in Venice, which he had long accepted for a variety of reasons. The great city of Rome, its cosmopolitan life and streets to stroll, and the diversity of its cultural opportunities provided new possibilities for Peiffer Watenphul. And yet, the little apartment and the studio in Rome again became a point of departure for many travels, to Lebanon and to Greece, to work at the International Summer Academy in Salzburg, and to Germany. Many of the new journeys to the South led to new solutions in paintings, new solutions of the sort just discussed above. And yet, another central interest of the painter was directed to Rome, his old love, to this city with vistas always presenting the classical image of Italy.

It is interesting to see how the painter’s new pictorial compositions on the theme of the city landscape, as developed by him both in portrait formats and with depictive strategies for extreme landscape formats, reappear in the Roman views of his late period. Rome, Forum Romanum I from 1960 is one example. Here, the architecture of Venice in an extreme portrait format is replaced with the continuous forms of ancient columns, with their verticals and cross-formations. In lieu of the close-up and long view across the canals, there is the close-up and long view into the fields of ruins in the classical Roman forum. The occasional space-generative elements are the diagonally situated remnants of columns and alignments of architectural elements that intersect one another like in the old techniques of stage scenery. The painter relies more than ever on harmonic pictorial solutions, on arranging and accentuating individual motifs; the extreme portrait format attests to this, as does the extreme landscape format of the Landscape near Paestum from 1960. The variations on the principal pictorial compositions allow the artist the opportunity to continue working in varying ways on already found solutions without working directly from nature. This may be an aspect of a more settled oeuvre, corresponding to the painter’s late work.

The painter brought his work to a masterly perfection in his last paintings of Rome in 1968. His painting Rome, View of the Pincian Hill is a compelling organization of the interdependence between near and far, the painting’s built-up layerings, and the connection between natural and built form. The view of the doubled layerings of the terraces on the Pincian Hill, the trees rising up in front of the horizon and the middle ground of the image, the green zones placed in front of the trees, and the upward-jutting columns and pedestals with statues are a classical composition of Italy seen and dreamt, something always close at hand for the artist. At the same time, the visualization of history in the present, the classical measure and the classical construction in these paintings is an invocation of what was increasingly being lost in the large cities and overcrowded tourist destinations of the South. It is an invocation of the original Italy, or of the image of this Italy that the artist carried with him. He summarized this in 1966: “My works have arisen through my love for the Mediterranean and its world. Those who love antiquity, the landscape with its olive trees and the silver foliage that is almost always changing, with its cypresses, the clear outline of its mountaintops, and its ‘purple gulfs’ will find this love in my paintings and be unable to evade its magic.” Werkverzeichnis, vol. 1, p. 76.

In: Max Peiffer Watenphul und Italien,exh. cat. for the eponymous exhibition at the Museo Nazionale di Castel Sant’Angelo (Rome, 2000); Edizioni de Luca, 2000.

© Prof. Ulrich Krempel. Reprinted by kind permission of the author.