Peter Hahn

“For now I’ll just Take Things in”: On Max Peiffer Watenphul’s Photographs

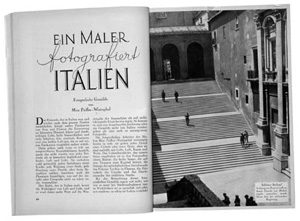

“A Painter Photographs Italy: Photographic Paintings by Max Peiffer Watenphul”: This was the headline under which the Berlin magazine Uhu published a series

of photographs in April 1933. It was one of the artist’s few photographic publications. Uhu, Berlin, vol. 7, Berlin (April 1933), p. 44. Photographic paintings: This seemingly contradictory term is fitting to the character of Peiffer Watenphul’s photographs. In taking photographs, the painter captured precisely the specific place and time, that is, the photographic moment. Simultaneously, he used artistic composition to attain an image of high atmospheric density—an artistic light-image. These are imagistic, subjective photographs. For this reason, it is appropriate to call them photographic paintingsbecause of subject matter and design elements they share with the artist’s paintings from the same period.

Today, Max Peiffer Watenphul is no longer unknown as a painter. He is sought after as a subtle interpreter of Southern landscapes, seemingly archetypal scenes with cypresses and pines under an Italian sky, with ancient ruins, temple remnants, columns, and statues. The artist, a humanist in the classic Romantic tradition, has created paintings with a distinctive, and often, with melancholic colors. Saturated by southern light, and strangely transparent, they unmistakably express the German longing for Italy.

That Peiffer Watenphul not only painted, but also took photographs is, however, not well-known. Apart from the outstanding catalogue raisonné,

Grace Watenphul Pasqualucci and Alessandra Pasqualucci, eds., Max Peiffer Watenphul, Werkverzeichnis, vol. I (Cologne, 1989), vol. II (Cologne, 1993), hereafter cited as Werkverzeichnis.

this aspect

of the artist’s work has been almost neglected in the now quite extensive catalogue of literature. This is understandable in view of the small number of attested photographic works relative to the wealth of his painted oeuvre. The catalogue raisonné records a mere sixty photographs as opposed to 800 paintings, 1426 watercolors, 1227 drawings, and even 126 works of graphic art. The photographic domain deserves a special appraisal, however, and not only because photography as a medium has enjoyed an explosion in appreciation over the past ten to twenty years. It is also because Peiffer Watenphul, although he may have pursued photography on the side and only from time to time, not least to make money, was thoroughly aware of the artistic merit of his photographs. Furthermore, as a former Bauhaus student, he could hardly have subscribed to the classic disdain for photography as less artistically worthy due to the instruments’ gravitation toward the merely depictive because to its technical apparatus.

Bauhaus-Archiv,

Museum für Gestaltung, Berlin

Certainly Max Peiffer Watenphul, who held a doctor of laws, was a Bauhaus student of a special kind. A lawyer who had completed all of his state exams and earned his doctorate with a dissertation on church law, he did not resolve to become a painter until after finishing his studies—a resolution he held to throughout his life, despite every setback and recurring financial problems. Paul Klee, whom he asked for lessons while in Munich, declined him, but later, became Peiffer Watenphul’s teacher at the Bauhaus. The latter man had already become aware of this new kind of art school in 1919; on arrival, he entered inevitably into the chaotic creative ferment of the early years. He took Johannes Itten’s preliminary course; certain beautiful studies survive from his time there. The Bauhaus required workshop labor, and he was in the potter’s workshop and the weaving workshop. “Gropius gave me total freedom to work in all of the workshops without remaining under a particular teacher. Thus, I worked under Itten, Klee, Marcks, the weaving workshop, ceramics.” Information given by Peiffer Watenphul as a response on a Bauhaus-Archiv questionnaire; original held by the Bauhaus-Archiv. The Council of Masters of the Bauhaus, in its session on December 6, 1920, nonetheless, called on Peiffer Watenphul to choose a workshop. Copy of the minutes held by the Bauhaus-Archiv. At the same time, he received the unusual privilege of his own studio. Art, understood as painting, may have been the most powerful driving force at the Bauhaus, but the school’s goal was hardly the training of artists. That the founder of the Bauhaus, then, would give Peiffer Watenphul his own studio must mean that Walter Gropius sensed the latter’s exceptional talent, and how he readily assimilated what was emerging there with verve, often through struggles and contradictions, even as he made his way as a painter, in spite of his ephebic appearance, and not without first successes. The fundamentals of design taught by Itten, such as contrasts in brightness, form, and color, and the investigation of the characteristics of different materials may all have influenced his later work, not least his photography. Itten gave notice in 1922, after fierce conflicts with Gropius, and he left the school in 1923. As a parting gift, his students gave him a tapestry woven by Peiffer Watenphul that represented the formal and design aspects of Itten’s teaching in textile form: A lovely gesture for the departing Bauhaus master, as well as recognition for a very special student.

It was only after Peiffer Watenphul’s departure that the much quoted “Unity of Art and Technology” became the motto of the Bauhaus, on its way to Industrial Design. Yet, Peiffer Watenphul hardly spurned the technical aspects of art. Among other things, immediately after his departure from the Bauhaus, he set up an enamel workshop in Salzburg together with the Bauhaus student Maria Cyrenius. Though an artistic nomad who seldom stayed in one place for any length of time, Peiffer Watenphul was to remain friends with Cyrenius throughout his life. The correspondence between Peiffer Watenphul and her provides a highly valuable source of information about his artistic and personal path.

private collection

Peiffer Watenphul began taking photographs around 1924. A series of photographs are extant from his six-month journey to Mexico. These are mostly autodidactic photographs, “snapshots” seemingly conceived to capture personal impressions, but the series also includes studies of remarkable photographic quality.

private collection

Bauhaus-Archiv, Berlin,

on loan from a private collection

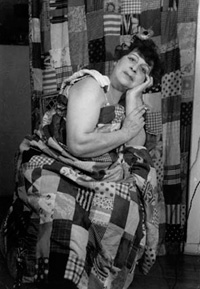

Peiffer Watenphul learned photographic technique in the stricter sense while teaching at the Folkwangschule in Essen from 1927 until 1931. He was hired to teach a fundamentals course, which, it may be assumed, closely followed the model of Itten. “I was the head of a preliminary course”, Peiffer Watenphul said of it, laconically. Information given by Peiffer Watenphul as a response on a Bauhaus-Archiv questionnaire. His pupil Heinrich Goertz offered a retrospective account of this teaching: “Mein Lehrer Max Peiffer Watenphul,” in Hannoversche Allgemeine Zeitung, weekend supplement, January 2 and 3, 1971. Max Burchartz, also teaching in Essen at the time, taught him the craft of photography. From this period in Essen comes the portrait of the artist’s sister Grace in 1927. A roughly contemporary study, “Peiffer Watenphul while Photographing,” may have been created by self-timer, though it is also possible that the shutter was triggered by someone else, such as his sister. The position of the head and fingers suggests that this photograph is a pantomime presentation of the use of a 35 mm camera, possibly a Leica. It has not been possible to determine with certainty what cameras Peiffer Watenphul worked with in later years. For the most part, Peiffer Watenphul appears to have used a 35 mm camera, as would have been suitable for someone constantly traveling. Glass negatives exist for certain photographs, however, indicating the use of a plate camera. A remarkable series of portraits, likewise from the period in Essen, depicts his fellow Bauhaus student Grete Willers. These portraits, like Peiffer Watenphul’s other portraits of women, are highly staged: The women present themselves profusely adorned with hats, veils, necklaces, fruits, and fans, and often garishly rouged, the women taking obvious delight in costuming themselves. The photographer also seems to have reveled in capturing, in a painterly and sensual fashion, opulently costumed women. Peiffer Watenphul did not idealize, however, nor did he shrink from traces of decay and the depiction of aging; one example is the late portrait of Johanna Ey. Some of the portraits, termed Grotesques, show men in women’s clothing. The transvestite element may have had special resonance with the artist’s homoerotic inclinations. “Have taken new glittering photographs. But as they say, very perverse!!?” Letter from Hattingen, Christmas 1932, to Maria Cyrenius, in Werkverzeichnis, vol. II, p. 26. We do not know whether this remark related to the aforementioned sitters. It is certainly conceivable, since transvestites, lesbians, and gays were long considered “perverse.”

private collection

The first published photographs of Peiffer Watenphul brought him a substantial measure of acclaim. The international exhibition Das Lichtbild(The Photograph), mounted in 1930 at the Deutsches Museum in Munich, presented a 1930 portrait of Grete Willers with a cigarette.

Catalogue of the international exhibition Das Lichtbild, organized by the Münchner Bund and the Verein Ausstellungspark München e.V. in Munich, 1930.

The study group for the exhibition numbered, among its members, Wolfgang von Wersin, Paul Renner, and Franz Roh.

A portrait of Grete Willers with a veil, and two other photographs appeared in the Paris journal arts et metiérs graphiquesin 1931.

Arts et metiérs graphiques, Paris, no. 24 (June 1931).

Peiffer Watenphul reported from Italy in 1932: “I am enjoying such great success with photographs in Germany. Always very good reviews. Now purchases in Lübeck.”

From Rome in 1932 to Maria Cyrenius, unpublished letter, MPW Papers.

Peiffer Watenphul practiced the photographic métier extensively during a long stay in Rome in 1931 and 1932, a stay that was decisive in his later life and artistic work. In 1931, Peiffer Watenphul was awarded the Prize of Rome, which brought with it an invitation to the Villa Massimo. The artist was able to pursue his interests free from financial concerns for the first time. “Freedom is so magnificently beautiful. No one says anything to you. I am enjoying every hour—for it will never be this way again.”

From Rome in the autumn of 1931 to Maria Cyrenius, in Werkverzeichnis,

vol. I, p. 29.

The consciousness of the ephemeral makes the present precious. With this journey to Italy, not his first, but the decisive one for his artistic development, Peiffer Watenphul found the subject matter for his life. The themes for the photographs he created at that time are Mediterranean landscapes and cities, like those of his paintings. His Roman photographs, indisputably the centerpiece of his photographic oeuvre, depict the legacies of antiquity. “I love Italy more than words can say … Am painting all terraces and ruins with statues in between. Trees with dark foliage. Am photographing a great deal.”

From Rome in the spring of 1932 to Maria Cyrenius, in Werkverzeichnis,

vol. I, p. 31.

It is hardly possible to describe his motifs more succinctly. One can merely add that the ancient scenery in his photographs, as in the paintings and watercolors dating from the same period, has something theatrical about it. All this held an immense fascination for him, and in his wanderings through Rome and in the numerous excursions he took into the countryside, and later to Florence and Naples as well, he formally imbibed what he saw. “For now, I’ll just take things in,”

From Rome, in the autumn of 1931, to Maria Cyrenius, in Werkverzeichnis,

vol. I, p. 29.

he wrote shortly after his arrival in the autumn of 1931. Peiffer Watenphul may not have meant this “photographically” [the German verb aufnehmencan mean both to take in impressions in general, and to take photographs in particular—TRANS.], but a reinterpretation in that sense is permissible. Peiffer Watenphul, like most of the important German visitors to Italy from Winckelmann and Goethe onward, was primarily interested in ancient Rome and the Renaissance. His photographic motifs are also similar to those that have made their way into the photographic gaze in ever-new ways from the nineteenth century to the present:

Gesine Asmus (ed.), Rom in frühen Photographien: 1846–1887(Munich, 1978).

The Capitol and the Capitoline Museum, the Forum Romanum, the Roman fountains, the Roman gardens, the papal churches, and the Ostia Antica.

Bauhaus-Archiv, Berlin,

on loan from a private collection

“I find Rome more beautiful and more magnificent by the day,” he wrote in December of 1931, adding: “I still have not photographed anything at all.” From Rome, in December 1931, to Maria Cyrenius, in Werkverzeichnis, vol. I, p. 29. Yet, soon thereafter: “Am photographing a great deal,” he reported in 1932. From Rome in April 1932 to Maria Cyrenius, in Werkverzeichnis, vol. I, p. 31.

As in his paintings, so in his photographs Peiffer Watenphul succeeded in creating an unmistakable atmosphere and capturing the magic of a given situation. Some of the photographs give the impression that the artist placed less emphasis on technique, for example, on sharpness of focus, than he did on artistic impression and composition. The occasional fuzziness of his images, when not a result of the photographic materials (the originals of which are not always extant), does not seem to have bothered him. Peiffer Watenphul even seems to employ fuzziness as a stylistic means, as in a photograph taken during an excursion to Florence in 1932 in which the shadow of a passer-by hurries through the scene in front of the Florence cathedral. Is it perhaps a photographic coincidence or a powerful visual symbol juxtaposing fleeting modern man with the timelessness of art? Peiffer Watenphul pays careful attention to contrasts of brightness and material, as in the extreme contrasts of brightness in the evening photograph of San Giovanni in Laterano of 1932, and also in various similar night photographs. He is equally exacting in his attention to composing images, which, despite the movement (as in the image of persons going up and down the sun-drenched Capitoline stairs of 1932), leave nothing to chance. Here, one may infer, the principles of design that Peiffer Watenphul acquired at the Bauhaus, in particular from Itten, were bearing fruit.

Peiffer Watenphul must have had the publication of his photographs in mind from the beginning of his Roman journey, and must likewise have had publication in mind on later Italian journeys. He also placed some of the material with journals For example, in Uhuas noted above (1933), vols. 7 and 8. and the Ullstein picture service. “I sold five photographs to Querschnittand Neue Linie—but I have not yet received payment. I hope I can mount exhibitions in Berlin and possibly earn something from photographs,” From Hattingen, Christmas 1932, to Maria Cyrenius, in Werkverzeichnis, vol. II, p. 32. he wrote to Maria Cyrenius in late 1932—a hope that did not meet with much fulfillment.

Peiffer Watenphul was in Rome for the festivities in 1932 on the occasion

of the one-hundredth anniversary of Goethe’s death. The anniversary was commemorated with a volume collecting Goethe’s letters to Charlotte von Stein and his Italian Diary, and illustrated with photographs of Rome by Peiffer Watenphul, and others. The use of the “modern” medium of photography in a book devoted to the classical Goethe apparently required justification. Adolf Behne, who had chosen the photographs and was one of the most important mentors of modern design in Germany, wrote, “The experiment was not without its perils. To present nature free and pure from contemporary taste is possible only through the camera … and the objective and sensitive disposition of those who direct and configure the camera. This is because the natural, elementally penetrating photograph does not come about automatically. Here, too, simplicity is the last, and not the beginning.”

Goethe. Briefe an Frau von Stein nebst dem Tagebuch aus Italien und Briefen der Frau von Stein, vol. 2, Deutsche Buch-Gemeinschaft, ed., Berlin, undated (presumably 1932), including photographs by Max Peiffer Watenphul on pp. 15, 16, 18, 20, and 25. Adolf Behne’s afterword on the choice of photographs appears on pp. 533–36.

So it is, and Peiffer Watenphul’s ability to achieve this simplicity cannot be denied.

Upon his return from Rome, Peiffer Watenphul was tireless in visiting various publishers. He related from Berlin in 1933: “I am running around a great deal to sell my photographs. Have made sales to Uhu, Woche, Magazin, Neue Linie (which will be printing a beautiful photograph in the March issue). It is all awfully hard! But at Ullstein, I am very popular. For the Berliner Illustrierte, they have commissioned me to take photographs of the Pergamon Altar—which I am currently attending to.” From Berlin in 1933 to Maria Cyrenius, unpublished letter in the MPW Papers. It is not known whether anything came of this; no relevant photographs have been attested to this venture.

by torchlight, 1934

Bauhaus-Archiv, Berlin,

on loan from a private collection

There was even a Rome book planned with photographs by Peiffer Watenphul. After returning to Rome, he wrote in the winter of 1934: “Have photographed a great deal and created, in part, very good things with which I would like to publish an album in Paris.” From Rome, in the winter of 1934, to Maria Cyrenius, unpublished letter in the MPW Papers. Among the photographs of 1934 were night photographs of St. Peter’s by torchlight, doubtless, among the best works in his photographic oeuvre. “St. Peter’s has been illuminated since Monday. I find it to be, time and again, an utterly undreamt-of drama. I took six night photographs of it…. Have photographed an enormous amount more.” From Rome in April 1934 to Maria Cyrenius, in Werkverzeichnis, vol. I, p. 35. He may have had hopes for Paris on the basis of his friend Florence Henri, who was living there. She visited him in Rome and took photographs in Rome herself (and Peiffer Watenphul made multiple portraits of Henri). Florence Henri: Artist Photographer of the Avant-Garde. Exh. cat. San Francisco (1990), pp. 52–53. Yet, nothing came of the book, in Paris or in Berlin, where Peiffer Watenphul had also made inquiries. ”My photo book on Rome will not be published, then,” he reported in 1935. “I have negotiated with all of the publishers, but the state of the book market, in particular, the market for photo books is so bad that no publisher can dare to try something like this. This grieves me very much because the collection on Rome is something thoroughly new and verybeautiful as, indeed, everyone tells me.” From Hattingen in 1935 to Maria Cyrenius, typewritten letter in the MPW Papers.

That was 1935, and the disappointment resulting not least from the circumstances of the Nazi years seems to have dissuaded Peiffer Watenphul

from further photographic efforts, at least with an eye to publication.

Peiffer Watenphul continued to take photographs all the same, although no longer in a systematic way. The landscapes he visited on his numerous journeys, in particular, the Italian coasts he loved so much—Positano, Ischia, and Gaeta, to name a few—he preferred not to photograph with a camera, but to sketch out in drawings. Peiffer Watenphul continued to take photographs of his private circle of friends and acquaintances. Some of the resulting photographs are of remarkable quality. Examples include the seemingly highly artificial portrait made of the writer Herbert Schlüter while he was living in Italy as well as a series of photographs of a young Italian whose poses emanate an erotic intensity reminiscent of the work of Wilhelm von Gloeden, who had photographed along the Italian coasts thirty years earlier. “There are festivals in the evenings with fireworks and music…. The sea is exquisite, and everything inhabited by young gods,” From Gaeta in August 1932 to Maria Cyrenius, in Werkverzeichnis, vol. I, p. 32. Peiffer Watenphul jotted down in 1932. Something of this attitude to life is also expressed in these more private photographs, a selection from which we have chosen for inclusion in this book.

Peiffer Watenphul’s known photographs come predominantly from those owned by his family. His letters and the references highlight his intensive photographic activities as well as his efforts to publish these photographs. It seems astonishing that more of them have not survived. One must bear in mind, however, that Peiffer Watenphul’s place was completely bombed in Krefeld in 1943. According to his family, his entire photographic holdings were destroyed. It is not impossible that additional, as-yet unknown photographic works by Peiffer Watenphul still exist somewhere. The initiators of this exhibition would welcome any information in this regard. Please send any information to: Bauhaus-Archiv, Klingelhöferstr. 14, 10785 Berlin, Germany.

A Painter Photographs Italy, and this painter once termed his photographs to be “playing around alongside the painting.” From Rome, in the spring of 1932, to Maria Cyrenius, unpublished letter in the MPW Papers. This holds true to the extent that Peiffer Watenphul always felt himself, without exception, a painter, and pursued photography as something of a sideline, not least for financial reasons. Yet, this in no way diminishes the artistic merit of his photographs.

Bauhaus-Archiv, Berlin,

on loan from a private collection

Postscript. After the Nazi years and the war, an article was published in 1950 in the journal Kunstwerk, entitled “Das Romerlebnis von Winckelmann bis Rilke”: a sort of classical-humanistic breviary of quotations on German visitors’ experience of Rome that incorporated four large-format photographs of Rome by Peiffer Watenphul. Das Kunstwerk, year IV, vol. 1 (Baden-Baden, 1950), pp. 10–18. This reminiscence of his prewar photographs remained, however, an isolated instance. Apart from the personal and family realms, the artist had turned away from photography. He even sold his camera out of financial necessity during the postwar period he spent in penury in Venice. Personal communication from Alessandra Pasqualucci. Nonetheless, one more remarkable series of portraits came about in 1953, when he created new portraits of his friend Florence Henri, who had already sat for him as a model in Rome in 1932.

In: Max Peiffer Watenphul. Ein Maler fotografiert Italien 1927 bis 1934. Peter Hahn, ed., exh. cat. of the eponymous exhibition at the Bauhaus-Archiv, Museum für Gestaltung (1999).

© Dr. Peter Hahn

Reprinted by the kind permission of the author.